Transforming a struggling West Los Angeles shopping mall into a creative tech office campus, now known as One Westside, takes vision and a sense of place. The project, a joint venture between Hudson Pacific Properties, Inc . (NYSE: HPP) and Macerich (NYSE: MAC ), is a case study in adaptive reuse and its ability to give back to a neighborhood.

The two companies bought the Westside Pavilion mall in 2018 with the intention of repurposing the property. Hudson Pacific owns 75% of the venture and serves as the property’s day-to-day operator and developer; Macerich owns the remaining 25%. In January 2019, Google signed a 14-year lease as the sole tenant of One Westside.

Chris Pearson, senior vice president of development, planning, and government affairs at Hudson Pacific, has a personal connection to the project, having gone trick-or-treating in Westside Pavilion as a child. Despite those fond memories, it was clear to him and others that the mall’s heyday was a thing of the past. “When Macerich began looking at the opportunities to repurpose the mall, they came to the same conclusion that we did at Hudson Pacific,” he says.

David Short, executive vice president, asset management at Macerich, says the REIT’s fundamental vision for value creation is “to continue redefining our well-positioned, high-quality properties in attractive, urban, and suburban markets based on the highest and best use for each individual asset.”

In the case of One Westside, “the opportunity to co-create an adaptive reuse in place of a former enclosed mall with Hudson Pacific was an ideal match for the community, for Google as the long-term office tenant, and for us,” Short says. Macerich’s situation as the landowner allows it to wait until the right combination of factors is in place before it opts to move forward with redevelopment, he adds. “In this case, everything aligned for an exceptional project on an exceptional piece of real estate.”

Appealing Streetscape

Pearson isn’t the only Hudson Pacific employee with a tie to the former mall who has worked on the adaptive reuse project. Amy Pokawatana, vice president of development design, says her two sisters worked at Banana Republic at Westside Pavilion, “so I used to spend a lot of time there. We took photos before demolition started to remember the way it looked, but I knew the remodeled building would be a beautiful part of the urban fabric in West L.A.”

For the community, repurposing the aging mall created a more appealing streetscape, Pokawatana says. “Before, you wouldn’t want to walk along Pico Boulevard on the mall side because it was just one big blank wall,” she says.

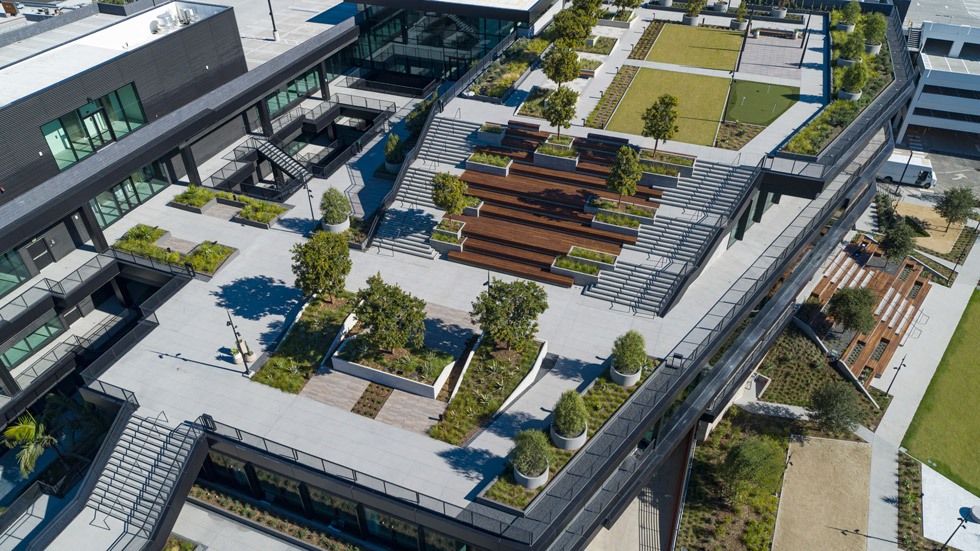

One Westside’s exterior is now nearly completely transparent with floor-to-ceiling glass. Terraces and a rooftop deck create a seamless indoor-outdoor office campus, which is especially appealing in the Southern California climate.

“We’ve done well with other adaptive reuse projects and have been able to find the benefits in an existing property, so we could see the opportunity with Westside Pavilion,” Pearson says. Adaptive reuse is more environmentally friendly and faster than ground-up development, he adds. “The underlying development allowed for office space without requiring a large environmental impact review. And the location and marquee history as a shopping mall didn’t hurt either.”

Light and Space

The redesign of Westside Pavilion adds a more vibrant anchor for the neighborhood.

Most large offices, especially in cities, are vertical and have limited outdoor access, Pearson says.

“From the beginning we realized that the shopping mall footprint offered an unusual ability to provide a ton of outdoor space,” Pearson says. “The shape of the building lent itself to creative office space. It’s the same size as a lot of tall buildings, but it’s horizontal.”

One Westside now has 584,000 square feet of flexible office space and 45,000 square feet of functional and lushly landscaped outdoor space including terraces and the rooftop deck. The terraces are accessed through 15-foot-wide folding glass doors that can be completely open for an indoor-outdoor environment.

“The three-story design allowed us to encourage travel via connecting interior and exterior staircases with access to a grand outdoor staircase,” Pearson says. A cascading staircase to the garden is deliberately designed to be conducive to outdoor meetings. “Especially as people return to offices, it’s important to have outdoor space for creative collaboration,” he says.

A unique aspect of the former shopping mall is the large, 150,000 square foot floor plates. Buildings with large floor plates historically are more sought-after than those with smaller ones because they provide options for office space, Pearson says.

“It’s hard to find that much contiguous square feet, which we realized provides a lot of flexibility for the tenants,” Pokawatana says. “The building is also a low-rise three-story building, so it was easy to envision a lot of light pouring into the space.”

Designed by architecture firm Gensler, One Westside also benefits from the mall’s original sloping floors. Although the slope had to be addressed with ramps and low steps, many areas in the building have extremely high ceilings that contribute to the light and sense of space in the offices, Pokawatana says. Ceilings are as high as 17 feet in some parts of the building.

“The mall had rooftop parking, so the finished building feels dramatically different because we opened half of the roof to create more open outdoor space,” she says.

The original shopping mall also had a central atrium and few exterior openings, which required significant demolition. “We essentially demolished the interior down to the columns and slabs and then rebuilt everything,” Pokawatana says. “We seismically upgraded the building which entailed adding almost 200 steel brace dampers. This required excavating concrete on the subterranean level, to install micropiles to support the new steel braces. We also upgraded the steel structure and fireproofing.”

Documentation of the building structure with the use of 3D modeling and augmented reality helped the team address discrepancies between the original drawings of the mall and changes made during its 30-year existence. Plans and documentation took one year, followed by two years of construction, Pokawatana says.